By Marianne Cooper, Ph.D., Clayman Institute for Gender Research at Stanford University

In their blog post, “New Research Shows Success Doesn’t Make Women Less Likable,” Jack Zenger and Joseph Folkman conclude from their analysis of assessments of men and women leaders who have come through their leadership program that “likeability and success actually go together remarkably well for women.” As a sociologist who focuses on gender, work, and family it is always nice for me to hear when things are going well for women at work. I mean wouldn’t it be great if this one analysis could disprove decades of social science research — by psychologists like Madeline Heilman at NYU, Susan Fiske at Princeton, Laurie Rudman at Rutgers, Peter Glick at Lawrence University, and Amy Cuddy at Harvard — which has repeatedly found that women face distinct social penalties for doing the very things that lead to success.

As the lead researcher for Sheryl Sandberg’s, Lean In: Women, Work, and the Will to Lead, I profiled this body of scientific research in her book. And what the data clearly shows is that success and likeability do not go together for women.

This conclusion is all too familiar to the many women on the receiving end of these penalties. The ones who are applauded for delivering results at work but then reprimanded for being “too aggressive,” “out for herself,” “difficult,” and “abrasive.” Just look at Jill Abramson, the first woman executive editor of the New York Times, who was described by staffers as “impossible to work with,” and “not approachable,” in a Politico article just days after the paper won four Pulitzer prizes (the third highest number ever received by the newspaper).

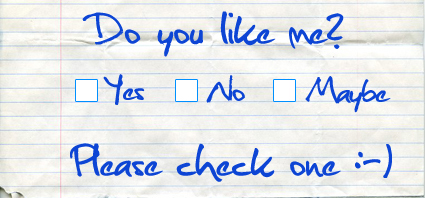

If likeability and success are negatively correlated for women, how then did Zenger and Folkman arrive at their conclusion? Setting other methodological concerns aside, it’s because they are not measuring likeability. Instead, their “index of likability” seems to measure interpersonal skills, which is an aspect of leadership ability, but not likability. The psychological research on success-likability penalties tells us that women and men can be viewed as similarly competent, yet still receive different likability scores. Scientific research also tells us that male and female leaders are liked equally when behaving participatively (i.e. including subordinates in decision making), which seems consistent with what Zenger and Folkman observe. But when acting authoritatively, women leaders are disliked much more than men. To be clear, it is not that women are always disliked more than men when they are successful, but that they are often penalized when they behave in ways that violate gender stereotypes. Being aware of this is important to truly evaluate what is really happening in companies and organizations — like the New York Times.

What is really going on, as peer reviewed studies continually find, is that high-achieving women experience social backlash because their very success – and specifically the behaviors that created that success – violates our expectations about how women are supposed to behave. Women are expected to be nice, warm, friendly, and nurturing. Thus, if a woman acts assertively or competitively, if she pushes her team to perform, if she exhibits decisive and forceful leadership, she is deviating from the social script that dictates how she “should” behave. By violating beliefs about what women are like, successful women elicit pushback from others for being insufficiently feminine and too masculine. As descriptions like “Ice Queen,” and “Ballbuster” can attest, we are deeply uncomfortable with powerful women. In fact, we often don’t really like them.

Given this field of research, Zenger and Folkman’s sweeping conclusion derived from a single analysis which used questionable methods that “likeability and success actually go together remarkably well for women” is indefensible. Moreover, their parting advice to young girls who aspire to positions of power that “it is totally your choice whether you act in a way that will have people continue to like you or not” flies in the face of scientific evidence which consistently finds that men and women doing the same thing are evaluated differently. If Jill Abramson were John Abramson we would likely be having a different conversation.

It is important to be right about these things. Getting it wrong obscures the real penalties women pay (i.e. not getting promoted, or being ousted) for simply doing what they need to do, and what men are allowed to do, in order to get to the top. Little girls (and little boys for that matter) would be better served by an informed conversation about gender stereotypes and how biased ways of thinking hinder both men and women from realizing their personal dreams and ambitions.

_____

Marianne Cooper is a sociologist at the Clayman Institute for Gender Research at Stanford University. She was the lead researcher for the book, Lean In: Women, Work, and the Will to Lead, by Sheryl Sandberg. Her new book, Cut Adrift: Families in Insecure Times (University of California Press) examines how families are coping in an insecure age.